All Eyes on ARG: Bodega Marine Lab’s Best-Kept Secret

Quick Summary

- The Aquatic Resources Group (ARG) helps researchers at the Bodega Marine Lab with resources they need to produce the best science.

- ARG is great at perfecting culturing techniques for aquatic organisms and has played a role in restoring a California native oyster to its natural habitat.

- The group is helping to address the urchin barren crisis along our coasts and are developing the handbook for urchin ranching that will make harvesting these creatures more profitable.

What does it take to study the ocean? It’s a lot harder than you might think, considering most marine research happens in a lab instead of the ocean itself. Imagine you are starting a project at Bodega Marine Laboratory (BML) and given only two weeks with limited funding to set up your study and collect all of the data you need to answer your research question. Data collection is an enormous task, but have you ever thought about the time it takes to replicate ocean environments on land? Researchers need access to a huge supply of seawater –often under very controlled conditions– and may also need access to marine life from intertidal or coastal waters that would have to be captured and brought back to the lab.

Fortunately at BML, the Aquatic Resources Group (ARG) is there to help! Small but mighty, this 4-person team of biologists and technicians is highly specialized in diving, boating, animal collection, and maybe most importantly, maintaining the lab’s elaborate seawater system, which pumps over 400,000 gallons of seawater throughout the facilities every day. If an incoming researcher needs heated seawater or 100 purple urchins for their study, ARG relieves some of the stress by working with them to design a perfect study system and collecting all of the resources needed to ensure the researchers can hit the ground running to gather their data when they arrive at the lab.

We often think of people who are good with plants as having green thumbs, but the members of ARG each have wet thumbs that are vital to the research at BML. They work behind the scenes 7 days a week, 365 days a year to safeguard projects and keep the animals in the lab alive. They are the first responders for many emergencies, so if a power outage halts seawater flow throughout the lab, ARG comes to the rescue, whether it is the middle of a busy work week or early Christmas morning when the lab is closed.

Their wet thumbs have also made the ARG team experts in culturing marine animals, proving incredibly useful for various marine conservation efforts, including the restoration of California’s kelp forests and native oyster populations. As a group, they work to develop the standard operating procedures (SOPs), or the “recipes,” for culturing different species. These “recipes” are then made available for anyone else around the world to “cook,” or replicate, and ultimately help humanity make wiser choices to protect our marine and coastal resources.

Restoring California’s Native Oysters through Aquaculture

One of ARG’s greatest success stories involves the recovery of California’s only native oyster species, the Olympia oyster (Ostrea lurida), whose population had been in decline since the 1920s. The story begins two decades ago when ARG documented a population of the rare oyster species while conducting an underwater environmental impact assessment at the San Francisco Airport. Over the next 20 years, ARG would become one of the first to collect and develop integrated techniques to support research on their wild populations and aquaculture efforts.

Fast forward to the present, ARG has concocted an elaborate recipe for culturing the Olympia oyster by the hundreds of thousands, making them available to aquaculture companies like the famous Hog Island Oyster Co. and conservation scientists interested in seeing the species restored to California’s coastlines. Joe Newman operates the oyster hatchery at BML on a day-to-day basis and has become an expert at growing these animals quickly in the lab for future outplant and research purposes.

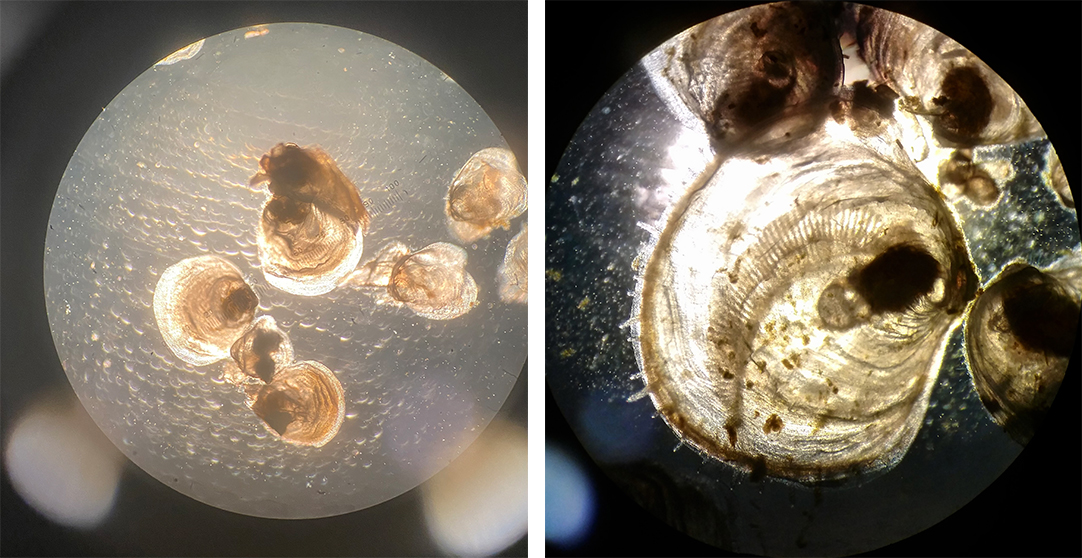

The first step in oyster culturing is facilitating reproduction, artificial maturation, between adult oysters by exposing them to warmer temperatures and ideal food sources, conditions that act as a spawning cue and cause adults to release their eggs and sperm into the water for fertilization. If reproduction is successful, hundreds of thousands of microscopic oyster larvae should be released into the tank, waiting to be collected and cultured until they are ready to settle into adult oysters.

ARG applies an intricate set of techniques to encourage larval settlement, after which babies will grow to a suitable size for outplanting. In the wild, oyster larvae will undergo settlement in response to a chemical stimulus wafting from the shells of nearby healthy adult oysters – using the presence of adults as a proxy for habitat suitability and their shells as a substrate for settlement. Rather than using whole adult shells for settlement in the lab, ARG has developed a more efficient technique for growth by spreading crushed adult oyster shells over a special settlement screen. Crushing the shells prevents overcrowding by allowing each baby oyster to grow on its own substrate, where it will eventually grow its own shell over the fragment.

As the oysters grow larger, they are rinsed and transferred through settling screens of different sizes to group similar-sized oysters together. After several weeks of care in the hatchery, the majority of oysters are prepared for transport to the oyster farm where they will be outplanted in their native habitat, Tomales Bay. Here, they will grow slowly over the next 3-4 years before they are big enough to be harvested for market sale. Though this may seem like a costly period to wait for profit, the outplanted individuals also contribute to the local environment by supporting the wild oyster population through reproduction, filtering the water of Tomales Bay, and providing habitat for other species.

Learn even more about this project in a video filmed and produced by Sam Briggs and featuring Joe Newman: The Native Oyster Restoration Project.

Saving Kelp Forests through Urchin Ranching

Let’s take a closer look at how ARG is helping to address the urchin barren crisis in kelp forests up and down California’s coastline. As you may already know, the combined impacts of marine heatwaves and disease outbreaks led to the dramatic decline in the state’s kelp forests beginning back in 2014. When the effects of extreme temperature and wasting disease joined forces to wipe out the purple urchin’s (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) biggest predator, the sunflower sea star (Pycnopodia helianthoides), it ignited an explosion in urchin populations. As it turns out, these spiny ocean grazers love to feed on kelp —so much that they have mowed down over 95% of Northern California’s Bull Kelp— converting miles of once bountiful forests to rocky urchin barrens.

Urchins dominate the seascape where kelps once used to thrive. Video by Sam Briggs (Lead diver and field operations manager for ARG).

The loss of these iconic kelp forests has also had far-reaching socio-economic consequences, stripping coastal fishermen of their livelihoods as habitat decline causes fisheries to collapse. California's abalone fisheries have been deeply impacted by this loss of habitat, bringing population numbers so low that the state has closed the recreational and commercial fisheries for the Red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) until at least 2026. ARG’s lead diver and field operations manager Sam Briggs recently captured this moving image of a lone abalone in the midst of an urchin barren. Surrounded by a sea of sharp spines, these hemophiliacs are having trouble competing with their urchin neighbors for an increasingly scarce food source, which has become a colossal barrier to the recovery of Northern California abalone populations.

Researchers believe that the road to recovery for our coastal kelp forests begins with widespread urchin removal — and what better way to reduce their population than by eating them? A market already exists for their rich, golden eggs (uni), but we have yet to see a commercial fishery established for purple urchins. We have their unique biology to thank for this, making these voracious herbivores incredibly resilient to starvation and allowing them to survive for years without food. As kelps disappear and urchin populations rise, urchins are prone to starvation and are forced to tap into their energy stores, eventually emptying themselves of the uni that makes them profitable.

ARG’s collection process of wild urchins off the coast. Video by Sam Briggs (Lead diver and field operations manager for ARG).

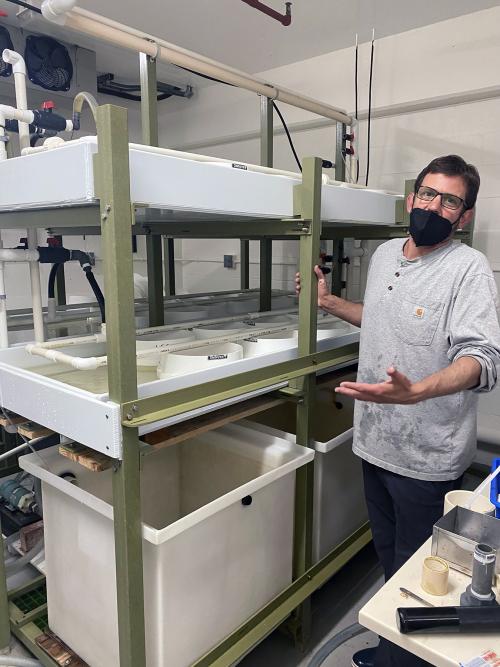

This is where ARG comes in, tasked with developing the SOP, or handbook, for urchin ranching — a strategy that involves bringing in empty urchins from the wild, placing them in a mock-up ranch, and fattening them up to cultivate uni that is ready for market sale. Right now, ARG is currently trying to figure out the minimum requirements that will yield maximum urchin growth at the lowest costs.

For anyone interested in building an urchin farm, costs will be an important factor. They might wonder how much they can reduce water flow or what the cheapest feed alternative they can use is before sacrificing efficient growth. ARG manager Karl Menard and team member Gabriel Tsuruta are currently trying to answer these kinds of questions at Bodega Marine Lab by looking at the effects of water flow and feed types on uni production.

The goal is to create a formula for urchin ranching that is available for anyone to replicate, all without breaking the bank while they get their business up and running. If ARG is successful, widespread adoption of their urchin ranching design would not only aid in the recovery of global kelp forests but would also reintroduce a viable source of food and income to local fishing communities that may have lost their livelihoods when the kelp forests began disappearing.

Thank you, ARG!

Though they often operate behind the scenes, the work and dedication of ARG’s core 4 –Karl, Sam, Joe, and Gabe– are at the heart of Bodega Marine Lab’s success as a leading research facility. As a jack of all trades for ocean research, the Aquatic Resources Group uses their expertise to facilitate cross-disciplinary research and produce solution-based science that addresses the world’s ocean conservation and environmental justice challenges. The creatures and researchers of the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory wouldn’t be the same without their expertise and support.

About the Author:

Sierra Cannon is a double major in Marine and Coastal Science and Environmental Science and Management graduating in Spring 2022. She is passionate about marine conservation and likes to spend her free time by the ocean. Sierra is looking forward to pursuing a career that combines public outreach, environmental justice, and marine resource management.