Empathy as a Universal Language

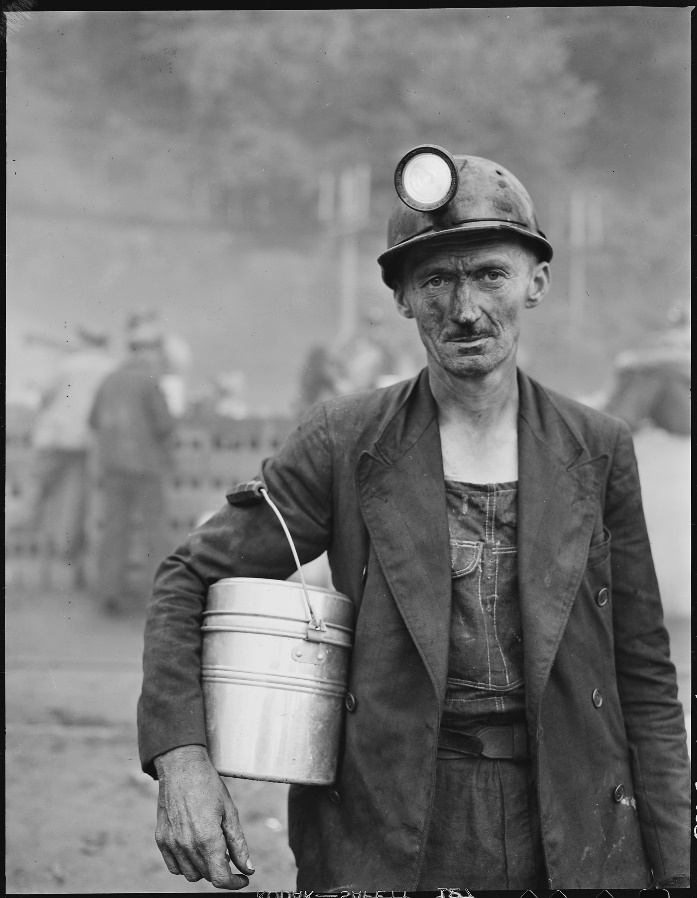

In spite of the environmental disasters that are caused by mining and burning coal, I cannot help but be at least a little fond of it, if only for selfish reasons. For the last 300 years, coal work has provided a livelihood for my relatives—I have the family name of Collier to attest to this fact. During an age when people adopted their trade as a last name my relatives were employed as Colliers, or coal miners. I come from a line of Colliers dating back to the 1700’s with relatives working in coal in western Europe before immigrating to America.

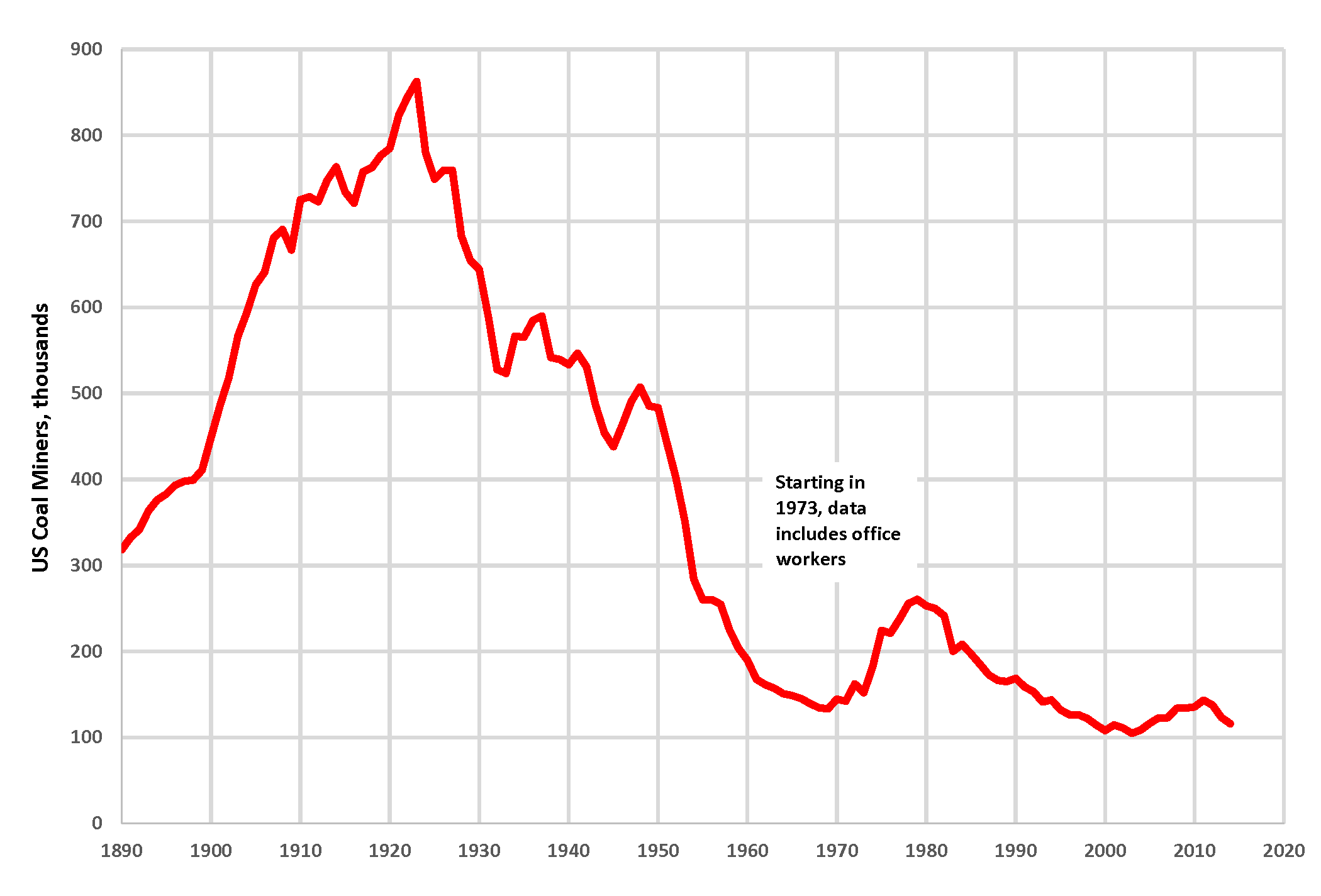

My family’s story is the story of coal and the American Dream, where workers believed hard work could translate to economic freedom. Nearly one million people a year were involved in mining coal at the peak in the 1920’s. These jobs provided a stable source of income that did not require an extensive skill set for native-born and recently arrived immigrants. However, coal mining was a dangerous profession fraught with lax worker regulations and precarious mine construction. The lives of coal miners became collateral for keeping up with the increasing demand for heating fuel and electricity that drove the greatest advances in the quality of life ever known.

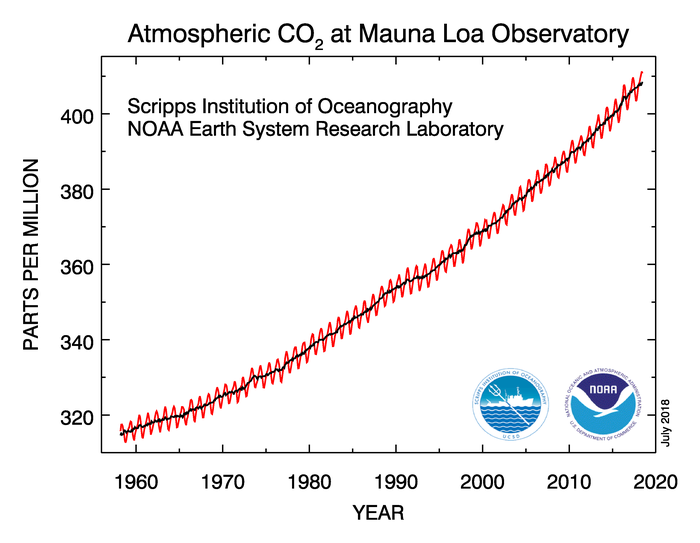

As the scientific process chugged along and coal burning was discovered to be a potent contributor to climate change, coal gained a dirty reputation and rightfully became a target for regulations. A new generation, my generation, has grown up with increasing alarm at the prospect of irreversible climate change and the coal industry a political issue. It wasn’t only coal that was vilified, but it was also the people who mined coal. Simultaneously revered and disenfranchised, coal workers moved from providing the fuel for the engines of the American economy to being unemployed en mass in economically depressed regions as green energy alternatives became more popular.

As a climate scientist, I study the consequences of increased oceanic acidity which is a by-product of fossil fuel combustion, but because of my coal connections I recognize the complexity of the human element of coal. My association with coal is not simple, but nuanced, filled with both rational and emotional connections for and against coal–and I don’t think that this is an uncommon position. In an increasingly partisan environment where dog whistling defines the political norm, we risk creating false dichotomies that pit coal workers against the environment.

Coal burning contributes to climate change and must be reduced, but it has historically provided a reliable livelihood for many people in impoverished areas. We should be more cognizant of the regional impact of reducing coal mining and empathetic to facilitate productive conversation. We need to lie down our verbal weapons and listen. Of course, this doesn’t mean that we have to agree with the decisions people make, but an awareness of why people feel the way they do fosters trust and allows these conversations to take place to develop solutions.