There’s a new detective in town:

SHERLOCK technology is reimagining species detection and identification in fish

Understanding species interactions and population dynamics are important for tracking the success and spread of threatened and endangered species. But how can scientists accurately track these data for species that look the same and cannot be identified via visual comparisons of two individuals? The answer may lie in the realm of conservation genetics and genomics. In addition to being able to provide species-level identification (and even individual-level identification), this field obtains and analyzes organisms’ genetic material to gain insight into population functions. Data obtained from genetic material can shed light on how isolated populations are from one another, how large populations are, and how populations are related to each other in time and space.

The Genomic Variation Lab at UC Davis, directed by Dr. Andrea Schreier, utilizes genetic and genomic methods in the context of fish and wildlife conservation. Their work is motivated by a desire to protect plant and animal populations by providing knowledge that can help wildlife and aquaculture managers preserve populations. Dr. Schreier’s lab has many areas of focus in which they work to achieve these goals, but two main ones are in tool development and sustainable aquaculture.

Tool Development: Making research safer and more accessible

One problem faced by scientists studying endangered species is that there are often restrictions that limit the organisms they are allowed to capture, handle, or take samples from for research purposes. Although taking a fin clipping from a fish doesn’t actually hurt the fish, it is often against the law to take tissue from an endangered species without proper permits and often the number of individuals that can be sampled under these permits is highly restricted by management agencies. So the question becomes, how can scientists accurately identify species if they can’t tell them apart visually and can’t collect tissue samples for genetic analysis?

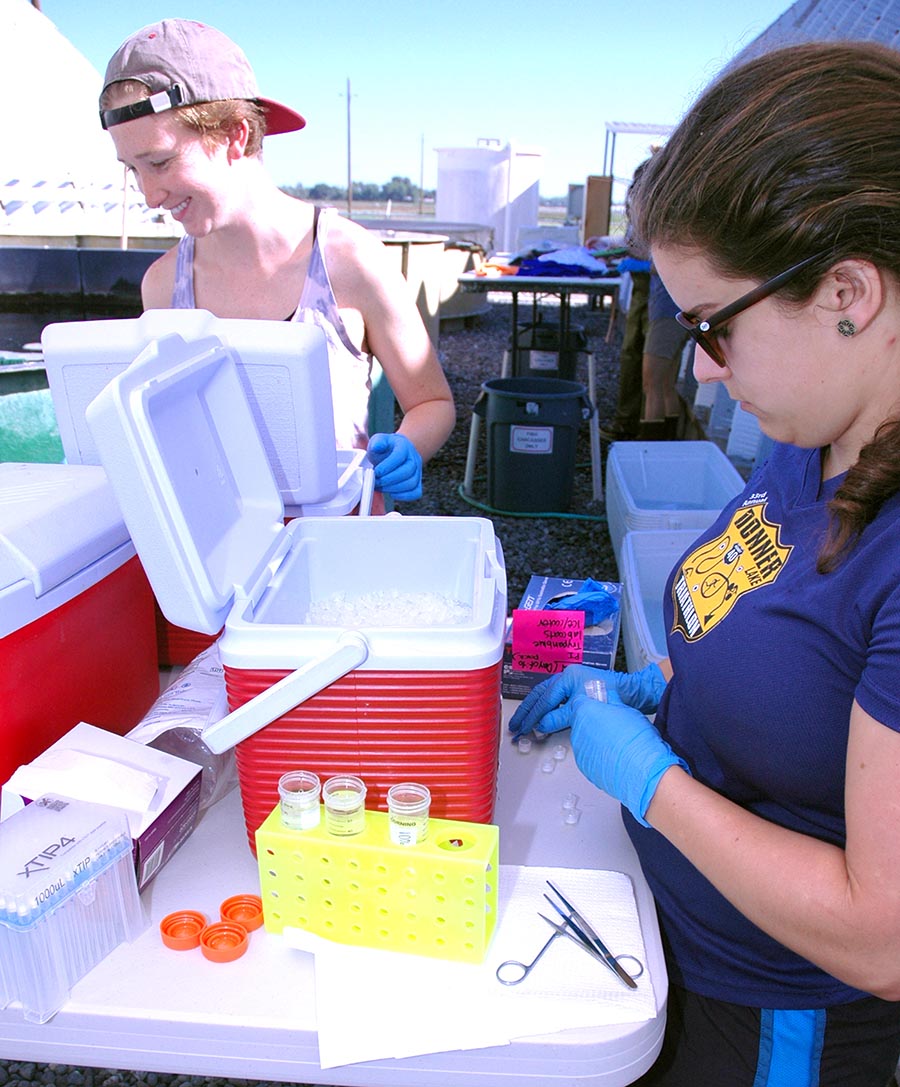

Dr. Schreier’s lab has recently tackled this problem head-on after hearing about a lab at MIT that used CRISPR-Cas13 technology for identifying pathogens in small biological samples. Although many people hear “CRISPR” and immediately think of the CRISPR-Cas9 technology that functions in gene editing, CRISPR-Cas13 is a different technology that can be used to identify species presence. Dr. Schreier and her lab, in collaboration with Dr. Melinda Baerwald of the California Department of Water Resources, are pioneering the use of CRISPR-Cas13 for this purpose by developing a tool called SHERLOCK (Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing), a non-invasive method of genetic analysis that can yield genetic sequence information from a swab of mucus off the side of a fish’s body in only ~30 minutes at room temperature. This is a huge improvement from other methods that involve obtaining a genetic sample (such as a fin clipping), extracting DNA from it, performing PCR (which takes a long time and requires many different temperatures for different steps). This process can take days to complete in the lab, depending on the DNA extraction protocol used, whereas this CRISPR-based SHERLOCK technology can be done in the field almost immediately.

Photo credit: Fred Conte

Once a researcher collects mucus from a fish’s scales, the DNA from the mucus is amplified in a process called recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). This step replaces the time-consuming and multi temperature-dependent process of PCR in other methods, which requires expensive lab equipment to perform. Next, the amplified DNA created during RPA is transcribed into RNA, then SHERLOCK technology deploys a guide RNA that identifies a species specific RNA sequence that CRISPR-Cas13 will act on. Once it identifies the correct portion of fluorescent-tagged RNA, it cuts it up into multiple segments, freeing the fluorescent probe and creating a signal. Researchers can then use a hand-held fluorescent reader to measure the fluorescent signal from this process and determine whether or not a species’ DNA is present in the sample. In addition to the increased ease and speed of result turnaround, this technology decreases organism handling time and risk, thus providing a safer way to obtain genetic material for analysis. This technology allows scientists to learn valuable information about wild populations while vastly reducing human impact.

Sustainable Aquaculture: Combatting spontaneous autopolyploidy in sturgeon

Another area that Dr. Schreier’s lab focuses on is sustainable aquaculture - the process of culturing and raising fish and other aquatic organisms in captivity for caviar and meat harvest so as to reduce the need for fishing wild populations of these species. Earlier on in her career, while obtaining her PhD, Dr. Schreier made a serendipitous discovery while working in white sturgeon aquaculture - she found that an unprecedented number of individuals exhibited a strange phenomenon: they had more chromosome copies than normal.

White sturgeon, which are highly prized for their caviar, typically have 8 sets of chromosomes (denoted as “8N”), which is different from humans and most mammals, who have 2 sets of chromosomes (2N). When white sturgeon spawn, the mother and the father each pass on half of their genes to their progeny, resulting in the creation of normal 8N offspring. However, Dr. Schreier found many individuals in multiple aquaculture farms that did not exhibit this 8N ploidy level. These differences in chromosome numbers were a result of spontaneous autopolyploidy, a phenomenon in which the mother passes on all of her genes to her offspring. In the case of white sturgeon, this means that the mother’s 8N egg combines with the father’s 4N sperm to create an offspring with a 12N ploidy.

Upon further investigation, Dr. Schreier realized that these strange 12N individuals were occurring at an alarmingly high frequency in aquaculture farms (~10%) compared to their frequency in wild populations (<1%). These observations led her to the questions: why is the frequency of spontaneous autopolyploids so much higher in captivity than in the wild, and what are the effects of this change in ploidy on the fitness and performance of individuals exhibiting it?

Key Takeaways:

- Genetic and genomic methods may be the key to species identification and population monitoring of threatened and endangered species.

- New CRISPR-based SHERLOCK technology can provide genetic sequence information quickly and easily using only mucus from the scales of fish. This allows for non-invasive sample collection and a safer human interaction with study organisms.

- Genetic analysis of individuals in captivity can inform aquaculture procedures, reducing the need for fishing wild populations.

After taking a variety of data on ploidy levels of white sturgeon in captivity and in the wild, Dr. Schreier and her team were able to get to the bottom of these questions. They found that the vigorous stirring of fish eggs during the artificial fertilization process used by farmers was actually the cause of the increased frequency of spontaneous autopolyploidy in captivity. They also found that although 12N fish (the product of spontaneous autopolyploidy) had no noticeable fitness or productivity differences compared to 8N fish, individuals with an intermediate ploidy of 10N (the progeny of 8N and 12N parents) did have fitness issues. Specifically, these intermediate 10N individuals often take much longer to produce eggs than most 8N and 12N females, which has a substantial effect on the success of aquaculture farms whose main product from white sturgeon is caviar, not meat.

Thanks to the work of Dr. Schreier and her lab, aquaculture farms now know how to go through the process of artificial fertilization while minimizing cases of spontaneous autopolyploidy. Dr. Schreier has also worked to sample fish from virtually every white sturgeon aquaculture farm and has successfully identified all of the 12N and 10N individuals in the population. Now, farms can harvest those individuals early and sell them for meat instead of spending additional resources on them in hopes that they will produce profitable caviar.

Future Endeavors in the Genomic Variation Lab

Dr. Schreier and her team are actively working to improve the CRISPR-based SHERLOCK technology. They are also developing new tools to use in eDNA (DNA from environmental samples like water) analysis, such as developing eDNA metabarcoding methods for monitoring of fish and macroinvertebrate species in the San Francisco Estuary.. Other projects in sustainable aquaculture of white sturgeon, as well as population monitoring of wild populations of sturgeon, are also underway. Dr. Schreier hopes to continue using genetic and genomic methods for fish and wildlife conservation efforts, as well as developing new tools to make doing so easier and safer.

Meet the Author: Jenna Quan

Jenna Quan is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in evolution, ecology, and biodiversity and minoring in education. She has a passion for ecology and biology, especially in marine systems. Upon graduation, she hopes to pursue a PhD in ecology and continue on in academia. When Jenna is not working on research projects at BML or in a genetics lab, she is co-captaining the UC Davis Dance Team and working on her knitting projects!