Springtime White Abalone Spawning at Bodega Marine Lab

A Brief History of White Abalone

Once abundant, white abalone were critically overfished in the 1970s. With the remaining wild white abalone so far apart from one another that they were unable to reproduce successfully, experts determined that captive breeding and outplanting were the best ways to save the species. After early breeding efforts were hampered by disease, the program headquarters moved to UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory in 2011.

Appreciating the impact public engagement can have in restoration efforts, lead scientist Dr. Kristin Aquilino and everyone on the program team have worked hard to connect a face (and an endearingly googly-eyed one, at that) to abalone conservation through social media, artwork, and mainstream media. These efforts have been rewarded with increased awareness of the plight of these marine snails and an outpouring of interest in and support of the program. Captive-raised white abalone were placed into the ocean for the first time in the fall of 2019, marking a major milestone in the recovery of this species.

A Recipe for Romance

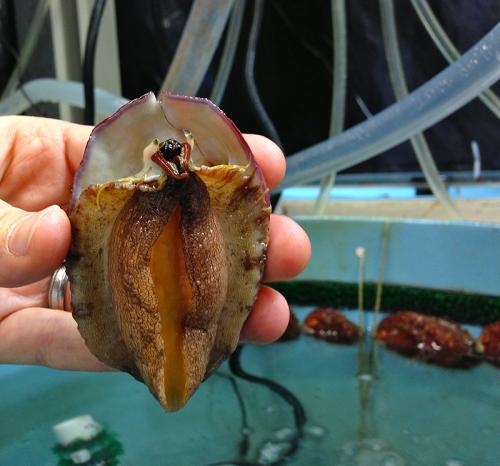

The White Abalone Team at Bodega Marine Lab are brewing up a love potion… but perhaps not one you’ll want to try out yourself. During spawning attempts like the one conducted on April 21st, 2021, a solution of hydrogen peroxide is added to individual buckets of abalone, encouraging the females to release eggs and the males to release sperm. Once those emissions are collected, they’re mixed at a precise ratio to optimize fertilization rates. If the embryos were in the wild, they’d sink to the bottom of the ocean but in the lab, their nursery for the first 24 hours is a bucket.

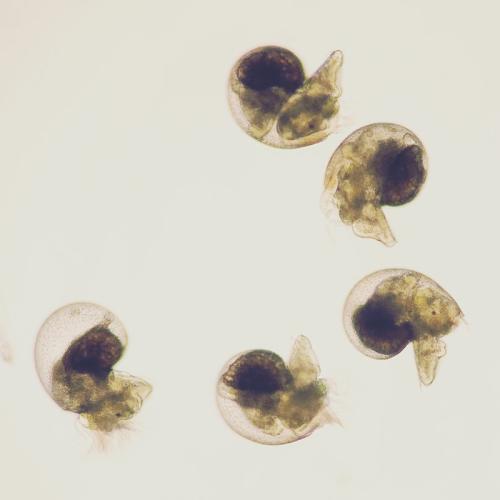

Once swimming larvae emerge, they swim in the water column for about a week. As Kristin Aquilino notes “It's interesting because it doesn't feed during that time, it relies completely on a yolk from its mom to get through that first week of life while it's swimming around.” When that first week ends, the larva must go through an intense, energetically-costly metamorphosis, which Aquilino likens to a caterpillar becoming a butterfly, except that instead of transforming from crawling to flying, white abalone go from swimming and not eating to crawling and eating for the first time.

Sadly, the team has to expect a high mortality rate during that time because the process depends on so many genes, and the correct ones, turning on and off for the transition to be complete, and the animals need to have gotten enough yolk from their mom to get through that first week of life and the subsequent metamorphosis. Typically, 95-99 percent of the animals die in their first month of life, a characteristic of this type of reproduction, but the ones that survive have an excellent chance of making it long term.

Airborn Abs

Following the first successful spawning attempt of this year on April 21st, millions of fertilized eggs were transported to partner facilities. A LightHawk flight, piloted by John Baker, took many to Long Beach, where aquaculture specialists from Aquarium of the Pacific, Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center, The Bay Foundation, and The Cultured Abalone Farm waited with open arms (and tanks) to receive them. Blythe Marshman drove embryos to Moss Landing Marine Laboratories the following morning, and one million eggs remained at Bodega Marine Laboratory. By April 28th, the teams across all 7 partner facilities and Bodega Marine Lab settled the larvae in their nursery tanks, where they could metamorphose into crawling snails.

A Boost, With Bated Breath

Because there was still ample nursery space left at the Lab and partner facilities, the team decided to attempt a “booster spawn” on April 29th, 2021 with 46 eight-year-old animals who they had not attempted to spawn this year. The “booster spawn” was successful beyond their expectations as far as the female white abalone were concerned, with 11 females spawning over 6.7 million eggs. However, it was equally unsuccessful on the male side, with no males successfully spawning.

Aquilino recounted to us the increasingly wild and desperate attempts of the team to get the males to spawn. You name it, they tried it: hydrogen peroxide baths? Check. Gonad massages? Yup. Enthusiastic, emulsifying-balsamic-vinegar-like shaking? Yes, that too. And we know we’re not alone in wishing that video evidence existed of these attempts.

Luckily, they were able to attempt fertilization with sperm aspirated from two- and 20-year-old animals. At first, things were looking bleak, with little motility visible in the sperm and only one embryo out of a few hundred observed cleaving after several hours. The next day, things seemed to be even worse, with only one hatchling out of 6.2 million eggs by the time the team expected hatching to occur. The situation took a joyous turn, though, when tens of thousands of larvae were spotted the next day.

A female white abalone spawning during the 4/21/21 attempt. Video credit: Kristin Aquilino/White Abalone Captive Breeding Program

The Mamas and the Papas

The five females that successfully spawned on April 21st were a mix of progeny from 2001, 2013, and one wild-origin abalone, bringing a diversity of genetic lineages into this spawning. The four resulting crosses were named Moderna, Pfizer, Astra, and Zeneca in homage to COVID-19 vaccine companies, with animals produced from the April 29th “booster spawn” receiving the name JandJ.

As Aquilino points out, the April 29th spawning may very well have been a first in white abalone captive breeding history, explaining that, to her knowledge, it’s the first time that viable white abalone larvae have been produced from strip-spawned sperm. She also points out that this is likely to be only the second time in the program that crosses of the “grandkids” of wild-origin abalone were reared through settlement. This is a promising development in restoration efforts, as it offers hope that the first animals to be out-planted, which were also second-generation captive animals, might produce viable offspring amongst themselves as well as with any nearby remaining wild-origin white abalone.

What Happens Now?

Even after settlement of all these new arrivals, Bodega Marine Laboratory still has open settlement space for 500k more and, according to Aquilino, there is additional settlement space at many of the partner facilities. This leaves opportunities for some partners to begin evaluating whether they have an interest and a capacity to attempt their own spawnings in the future, either with just their animals, or jointly with nearby facilities. Aquilino and her team are hoping to travel to partners later this spring to offer hands-on spawning support.

Be A White Abalone Conservation ‘Spawn-sor’

White Abalone Captive Breeding Program “Spawn-sors” help this program by helping to spread the word about the importance of white abalone conservation and through gifts that supply necessities. From seawater filters and UV sterilization bulbs to spawning chemicals and special tags to identify each baby white abalone, every little bit helps. By replacing overhead pipes with towering kelp forests and swapping submersible pumps for steady ocean swells, we hope our precious Aggie snails might save their species from the verge of extinction. It’s an incredibly exciting time for UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory's White Abalone Captive Breeding Program. We would love for you to be a part of the innovative and collaborative efforts to save this iconic marine species.

This program is made possible through funding from NOAA and California SeaGrant, the joint efforts of partners in the White Abalone Restoration Consortium (WARC), and through the generosity of donors.

Check Out Those Abs!

Follow White Abalone on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok

Join Dr. Kristin Aquilino on a tour of the White Abalone Facility at Bodega Marine Lab