8,000 Fish in 12 Days

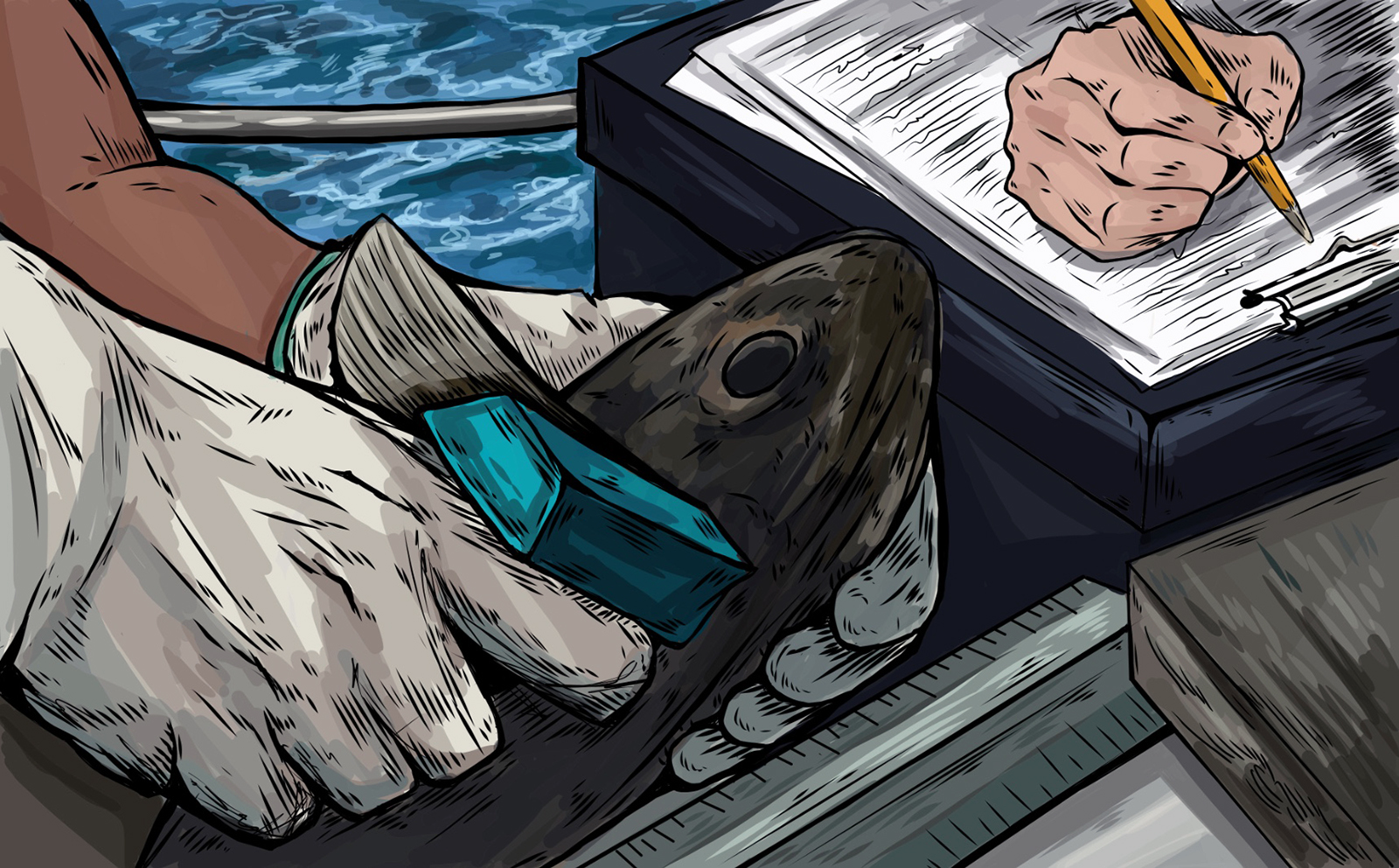

UC Davis Researchers and Local Anglers Team up to Study Marine Conservation

Quick Summary

- BML researchers form a valuable partnership with local fishers in this exciting volunteer experience with CCFRP.

“Are we gonna catch some fish today?”

“We’re gonna catch some goood fish!”

Jordan Colby and Francine De Castro are Master’s Students in the Toxicology, Physiology, Ecology and Conservation (ToPEC) Lab run by Assistant Professor Christina Pasparakis. They refer to the strong winds and rough weather of Bodega Bay as “Blow-dega Bay.” Leaving at six o’clock in the morning for a two-and-a-half hour mission, Colby and De Castro embark on a trip not only for research with other scientists, but for companionship with local anglers.

With funding from California Sea Grant, the California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program (CCFRP) provides an insightful volunteering experience with rockfish. The program operates along the California Coast with six institutions ranging from UC San Diego up to the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory (BML).

At the BML site, 12 trips were made last season to Bodega Head and Stewarts Point in the Northern Region. These places are Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), where strict limitations protect struggling local marine organisms as a method of environmental conservation. In the 1970s, “there was a lot of overfishing [for rockfish] and that crash really showed,” Colby states, “[MPAs] ensure that every species has respite from external fishing pressure.”

The entire program has caught about 200,000 fish across the coast in 2023 alone. At over 8,000 fish caught this last 2023 season, these boat trips out of BML have been some of the most productive.

An uncommon, but necessary bond

De Castro jokes about her seasickness out on the water: “The anglers and science crew play a game called ‘What did Fran have for breakfast?’ Well, when I have something like fruity pebbles, it becomes very obvious. They're like, ‘Oh, it's the rainbow.’”

When first entering the program, De Castro explains, “We were wracked with imposter syndrome because neither of us had worked in the ocean.” Through being transparent about their lack of knowledge as scientists, De Castro says that they established a trustworthy bond with their local angler captain. “It was good for our captain to see that we didn't come onto the boat with an ego,” De Castro expresses.

She states that some of these anglers have been fishing for over 40 years before the creation of MPAs. Due to the new restrictions of these areas, the anglers have told her that, “it gives them chills and vindication to [re-enter these MPAs] where they remembered the fish being active.”

As a first-generation Filipino woman surrounded by many white male anglers, De Castro has also feared feeling out of place. “Being able to represent myself in a way that felt true to my character was important to me,” she adds. She values how this community has put aside any biases about each other's backgrounds, both in experience and in culture.

“The ocean was an incredible equalizer,” De Castro reflects, “I don't want to call it an even playing field, but it was a meeting of the minds.” Colby adds, “Their knowledge in the field is amazing and invaluable to us as scientists.”

These trips also serve as a medium for scientists to informally communicate their research to the local community. “CCFRP is something that is accessible to anyone that can hold a rod and is willing to be out on the water,” De Castro emphasizes. Anglers will also often bring their families out on the trips.

De Castro mentions how “it’s common for anglers [to become] ambassadors for the program when they go back into their communities.” She explains, “Having someone, in a white lab coat, tell you ‘MPAs are good’ [is different] than having your Uncle Joe, at the dinner table, tell you he caught a [big] fish with scientists who work harder than he thought.”

After working with these anglers, Colby expresses, “I started to think about the historic social contract that society has had towards resource management. I've [now] thought about how to help shed light on the shortcomings of that contract.”

“These fish are sacred to us because they help us do the science that we need to do,” De Castro says, “but these fish are sacred to [anglers] because they’re a part of who they are as people.”

Colby and De Castro are extremely grateful for the service of the anglers and for their partnership. “All the anglers are volunteers. We literally couldn't do the projects without them,” says Colby.

Those interested in this fulfilling experience can find out more by signing up to be a volunteer with CCFRP. Entrance is free and no fishing experience is required, as shown by De Castro and Colby.

About the Author:

Elijah Valerjev, UC Davis class of 2024, is a Molecular and Medical Microbiology major with an Education and Professional Writing double minor. Interested in science communication, he enjoys the storytelling aspect of science writing, and is especially interested in connecting research topics to societal issues. Elijah works as board editor for the Aggie Transcript Undergraduate Research Journal, in addition to his work for the CMSI. In his spare time, he can be found enjoying his hobbies which include boxing, fiction writing and watching movies.

About the Illustrator:

Keila Alejos began her undergraduate studies at UC Davis in 2023. She aspires to combine both her passion for art and narrative illustrations with the insight of science or historical eras. Motivated by the opportunities at UC Davis, she is determined to learn and grow as both a scientist and artist with CMSI. Aside from the work being done for CMSI she also enjoys drawing her own series and ideas. On her days off, She often enjoys playing her bass, reading comic books, or her personal favorite, listening to loud music.