Sustainable Fishery Policy for a Resilient Future

Healthy ocean environments provide vital life support for roughly 3 billion people living in coastal communities worldwide. These vibrant ecosystems deliver numerous benefits to coastal communities that often rely on ocean industries such as commercial fishing for sustenance and income. The resilience of coastal communities and the fishing industry is an issue garnering global attention as fish stocks are pushed to the brink of collapse by combined pressures of overfishing, habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. As changing ocean conditions alter ecosystems, coastal communities and their associated fishing industry may be vulnerable to large social and economic shocks, especially in developing countries where many communities already experience extreme poverty.

The Future of Fishery Management

Scientists and policymakers are trying to find tangible ways to increase coastal resiliency, placing a special focus on improving fisheries management. Professors Dr. Matthew Reimer and Dr. James N. Sanchirico from the University of California, Davis are helping to inform these conversations by investigating fishery contributions to local economies from both a developed and developing country context. By identifying the pathways through which fishery activities enter and ripple through an economy, they hope to discover the aspects of coastal livelihoods that are most reliant on fisheries and influence policy that is designed to boost community resilience in the face of environmental change.

Coastal Resiliency in Developed Nations

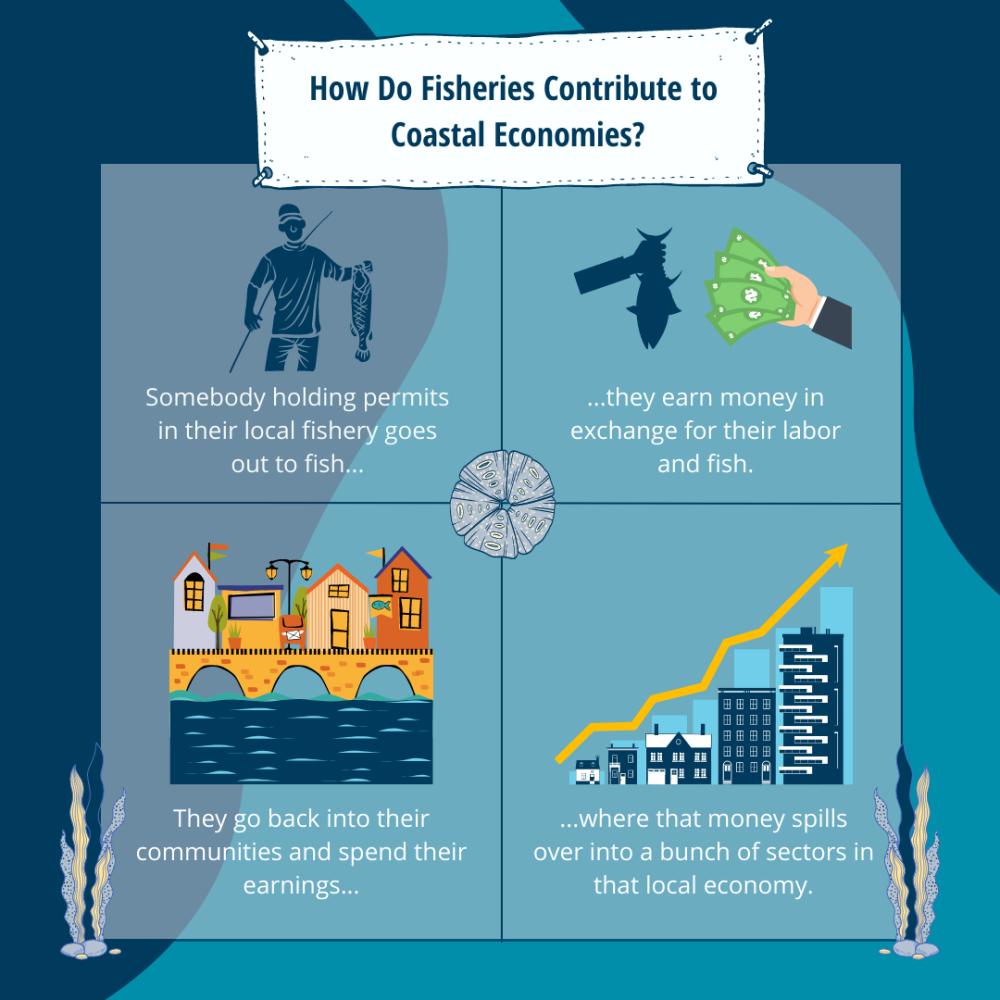

When fishermen return to port with their catch, how do their harvests create economic growth in the local economy? Policymakers often assume that commercial fisheries influence economies directly through local fish deliveries to nearby processors where the fish are gutted, filleted, and packaged for consumer purchase. These processors are thought to hire locals, generating new jobs and wages that boost the coastal economy. While little data exists to confirm local fish deliveries as having a significant economic impact, this narrative remains an important component of decision-making in fisheries management, raising concerns over the effectiveness of fishery policy in protecting coastal economies.

For the last 8 years, Dr. Matt Reimer ––Associate Professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Davis–– has served on the Science and Statistical Committee for the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council. This experience has exposed him to the biggest challenges facing Alaskan fisheries and has inspired him to investigate the roles of fisheries in Alaskan economies. His research offers some of the first empirical evidence of spillover effects from commercial fishing to other sectors of the economy. To his surprise, there was little evidence supporting the previous assumption that fish deliveries to local processors were an important contribution to economic growth. In fact, local deliveries created processing jobs that attracted temporary non-resident workers rather than local residents, resulting in very little spillover effects to other sectors. This meant that the location of fish deliveries (where fish were offloaded) didn’t serve any benefit to the local economy since the new jobs and wages were given to non-residents who weren’t members of that economy. Perhaps the most interesting outcome was finding out that the biggest spillover effects occurred when local fishermen took their earnings back to spend in their communities and not somewhere else, allowing it to ripple to other sectors of their local economy.

Reimer explains the significance of this in terms of previous fishery policies, which were designed to stimulate economic growth through “sustained landings” by forcing fisheries to deliver fish to certain communities as a strategy to maintain jobs in these areas. From his results, we know that where fish are delivered doesn’t matter nearly as much as what fishermen do with their earnings. “What you really need to do is create policies that incentivize people who own fishing permits to stay in their local communities so that they spend their earnings there,” Reimer suggests. In thinking about how this connects to building resilient coastal communities, it is important to confront policy inconsistencies like this one and redesign them to maximize a community’s economic potential and resilience.

What makes a community more resilient than others? Let’s consider what might happen to a fishing community if a sudden change in the environment made commercial fishing conditions unpredictable and prompted a fishery closure. Imagine three families: (1) one has a permit to the closed fishery, (2) the second has a permit to the closed fishery and a permit to another open fishery, (3) the third has a permit to the closed fishery, a permit to the open fishery, and another job in a non-fishing sector. If the fishery remains closed for one year, the first family is likely to suffer the greatest economic risk as opposed to the second who can still utilize their second fishery permit. The third is the most financially secure, holding permits to two fisheries and employment in a non-fishing industry, and will experience the least risk. Economists call this Portfolio Theory –– where making diverse investment decisions, like having multiple fishery permits and/or diverse sources of income, can minimize the likelihood and severity of shocks from any one fishery closure.

“It’s kind of like insurance –– by having a diversified portfolio of stocks, you ensure that if you get a negative shock in one, it is getting offset by a positive shock in another,” Reimer explains. His prior research analyzing Portfolio Theory risk-management strategies looked at whether fishing communities can diversify across fisheries, and additionally, whether they can diversify across different non-ocean sectors in the local economy to stabilize employment and reduce reliance on fisheries. As expected, communities with bigger or more diverse fishing permit portfolios experienced lower economic risk from revenue variability (i.e. financials remained stable) because they are not putting all their fish in one basket. In regions where it may not be possible to diversify portfolios because of limited numbers of fisheries, diversifying across non-fishing sectors might help mitigate a community’s susceptibility to environmental variability and reduce overall reliance on ocean resources.

Coastal Resiliency in Developing Nations

Coastal resiliency becomes more of a challenge in resource-dependent communities ––places with lots of fishing households–– in developing countries. Many people in these regions struggle with poverty and are extremely vulnerable to environmental variability because they rely on fisheries for income and food. Additionally, managing fisheries in these regions is especially difficult due to the lack of existing fishery data and the absence of institutions that could design and implement fishery management.

Key Takeaways:

- Coastal communities are vulnerable to changes in the ocean environment because their economies are highly dependent on ocean resources, such as the commercial fishing industry.

- If we want to increase the resilience of coastal communities, we should look to redesign fishery policy by tailoring them to address regional economic, social, and environmental challenges. Dr. Matthew Reimer and Dr. James Sanchirico focus their research efforts towards understanding the nuances of fishery contributions to local coastal communities.

- The influence of the commercial fishing industry on coastal economies is not “one size fits all,” especially when comparing communities from developed and developing nations. Instead, fishery policy design should be based on unique regional challenges and contributions made by fisheries to local economies. Policy improvements will help safeguard coastal communities against resource shocks and boost coastal resiliency in the face of climate change.

As in developed countries, there is an urgent need to develop a better understanding of fishery involvement in local economies. Dr. James N. Sanchirico, a Professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at UC Davis, has done research in Indonesia and the Philippines studying the ripple effects of policy decisions in fishing-dependent economies. Sanchirico explains that “the work in developing countries is at the interface of poverty alleviation, conservation, and the sustainable use of resources,” which makes designing sustainable development policy in these regions more complicated than in developed nations, where poverty and resource dependency are not as prevalent.

In the Philippines, Sanchirico and his team looked at the economic impacts of a poverty alleviation program and were surprised to find that it influenced the state of the local ocean environment, even though the program had nothing to do with marine policy. Through the use of cash transfer programs, they found that regular payments to poorer households caused an increase in fishing. As households acquired more income, more people could afford to eat fish which resulted in eventual stock declines of fish populations and a reduction in the benefits of the cash transfer program, or decline in income. Unsurprisingly, fishing households ended up suffering the biggest losses in income benefits. However, had the fisheries been better managed, the outcome may not have been so bleak, highlighting the urgent need for fisheries research in these communities to better inform their management decisions and increase their overall resiliency. As Sanchirico points out, the path to sustainable management is more convoluted in developing nations because it requires “finding the sweet spot where we can improve individual incomes and yet not overfish or overuse the resource.”

The Philippines poverty program is one case that shows how land-based policies could impact marine conditions. Another project of Dr. Sanchirico’s evaluated the effectiveness of sustainable development policies at achieving marine conservation goals and alleviating poverty in Indonesia. After analyzing both land-based and ocean-based sustainable development policies, he was amazed to find that an agriculture (land-based) policy had a greater positive impact on marine conservation than any of the marine policies. It turns out that the agriculture policy improved households that were involved in both fishing and agriculture, leading to increased efforts in agriculture and less fishing –– ultimately releasing pressure on the marine environment and allowing stocks to rebound.

Sanchirico’s work highlights a particularly important issue with our policy design strategies that have stemmed from the widespread perception that ocean and land environments are independent and non-interacting systems. After a careful analysis was done on the policies in Indonesia and the Philippines, the ripple effects of land-based policies on the marine environment became clear. Treating land and ocean as separate systems had unintended consequences and ended up further harming the communities that the policies were supposed to be helping. Moving forward with efforts to enhance coastal resilience in resource-dependent communities, policymakers will need to adopt the mindset that the oceans and lands are interconnected, and therefore must be treated as an interacting system in the policy design process.

About the Author:

Sierra Cannon is a double major in Marine and Coastal Science and Environmental Science and Management graduating in Spring 2022. She is passionate about marine conservation and likes to spend her free time by the ocean. Sierra is looking forward to pursuing a career that combines public outreach, environmental justice, and marine resource management.