The Intrepid, Evacuating Foraminifera who Survived a Wildfire

Through Smoke, Fire, and Evacuation

This study, titled Extensive morphological variability in asexually produced planktic foraminifera, was conducted by an all-female team of researchers: led by Kate Davis (a UC Davis Ph.D. Graduate who is now a postdoc at Yale) and Cait Livsey (UC Davis Earth & Planetary Sciences), and assisted by Hannah Palmer (UC Davis Earth & Planetary Sciences, and Bodega Marine Laboratory) and was conducted at the Bodega Marine Laboratory. It is a noteworthy story in part because of the hurdles faced by the team in order to collect this data. Starting in October of 2019, the Kincade Fire burned 77,758 acres of Sonoma County before its containment on November 6. As winds shifted on October 26th, moving the fire and the accompanying smoke-saturated air closer to the lab, Bodega Marine Laboratory was placed under a mandatory evacuation order by the county.

However, before leaving the laboratory, Ph.D. candidate Hannah Palmer was able to rescue the remaining living foraminifera and brought them in an insulated cooler to the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department on the UC Davis campus. This was important not only to keep them safe, but also to ensure that the team would be able to continue to observe and photograph them daily in order to gather the necessary data to complete the study. As a result, the foraminifera in this experiment have not only brought understanding of their species forward, but have survived a mass evacuation as well.

About the Publication

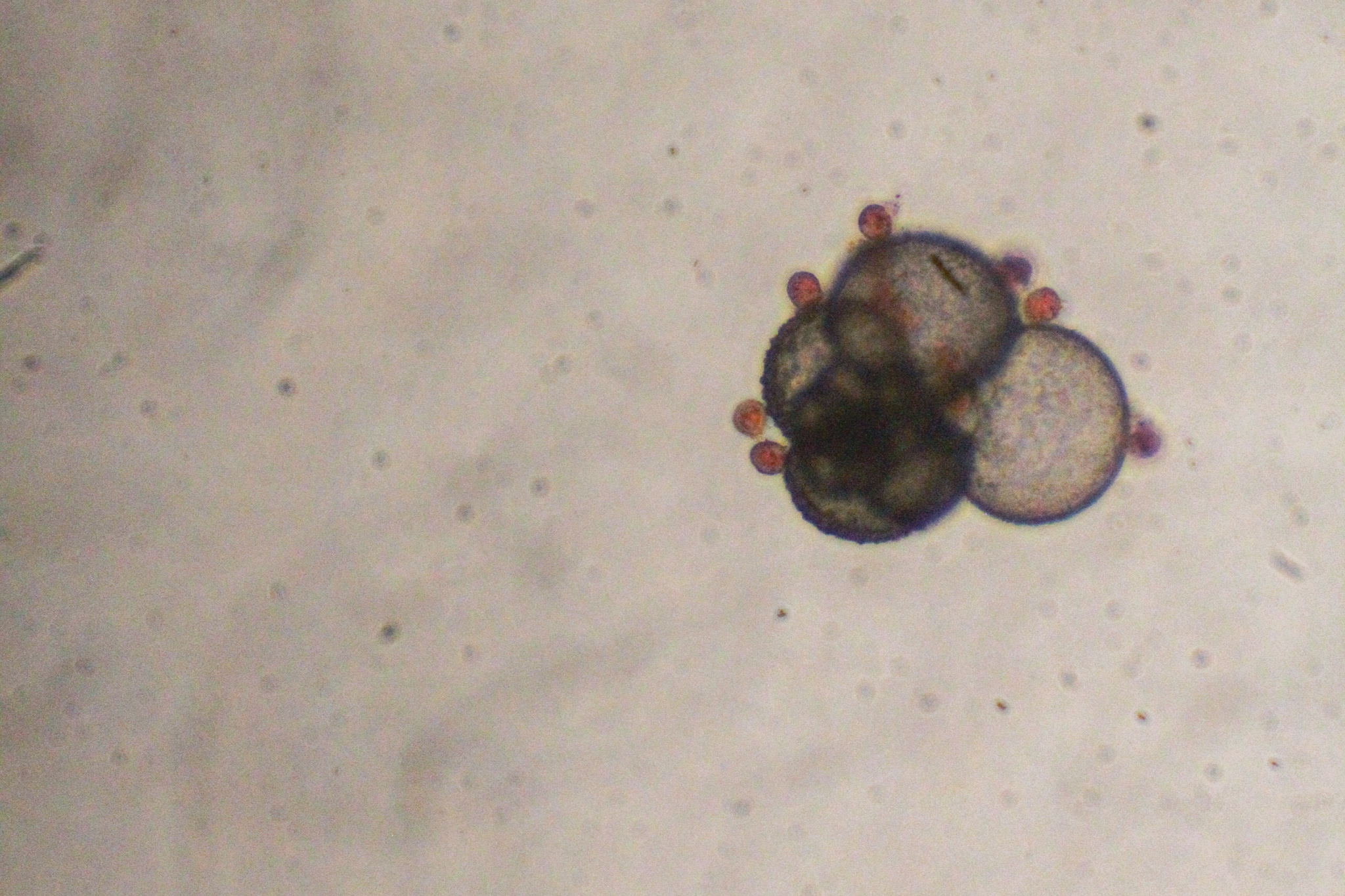

The ability of planktic foraminifera - a widespread and important plankton in the ocean - to respond rapidly to optimal conditions, even when populations are separated by great distances or where densities are too low for rapid population growth has long stumped oceanographers. By demonstrating the ability of Neogloboquadrina pachyderma to reproduce asexually, this study helps to close the gaps in understanding of planktic foraminifera and their ability to maintain genetic connectivity across distances and adapt to changing conditions. It also shows implications for the survival of foraminifera in a changing climate. Planktic foraminifera may be more resilient to global changes in the ocean since they are able to follow/track optimal conditions due to their more flexible reproductive strategy.

Important Takeaways:

Sometimes thought to only reproduce sexually, planktic foraminifera have now been demonstrated to reproduce asexually, although they tend toward sexual reproduction under culture conditions. This tendency could be explained by the influence of stressful and unnatural conditions, such as laboratory culture. It is suspected by the researchers in this study that the asexual reproduction observed was initiated prior to capture, which explains why offspring appeared relatively quickly after introduction to culture.

Morphological differences between offspring planktic foraminifera in the culture were observed, leading the team to note that, had these individuals been collected from tows, they would likely have been assigned to different species. The close genetic relation between these individuals suggests that these morphological changes are not the result of genetic diversity or large physical or chemical environment changes, but were responses to minute environmental changes in culture. This indicates that heritability among foraminifera may be low, especially among individuals exposed to environmental instability.

Why is this so important? “Typically it was thought that the different morphologies of this species reflected either different populations, or slightly different environmental preferences.” Livsey said, “The observation of numerous morphologies within the same environmental conditions and even further within genetic clones reveals that morphology is potentially less indicative than previously believed.”

When asked about the importance of this research Cait Livsey, one of the paper’s co-authors, explained that

“Planktic foraminifera are the primary tool that geologists use to study past oceans - most of what we know about past ocean temperatures, salinities, circulation, productivity, global climate, etc. come from planktic foraminifera fossil shells. In order to understand the controls on the geochemistry, diversity, morphology, etc. of planktic foraminifera, we study living ones in controlled environments to refine our understanding.”

Up until now, no planktic foraminifera had ever been documented to have reproduced in the laboratory so all studies on living forams had to be done on large individuals who were collected from the ocean using a tow net and brought back into the lab to study. As a result, the earliest stages of growth were never directly studied in the lab. So in addition to determining that these organisms could reproduce asexually, it was also exciting for the team because it allowed them to observe and document the earliest life stages of planktic foraminifera for the first time.

Read the full publication here

Here is a video of a daughter foraminifera moving across the bottom of the culture vial by use of its rhizopodial network. The streaming cytoplasm can be seen along the threads of rhizopodia and within the shell itself. Video has been sped up 20x and is magnified at 20x.