Where has all the bull kelp gone?

Under the unseasonably warm June sun with the Seattle Space Needle as our reference point, Dr. Jamey Selleck and I don our thick wetsuits. The air may be warm, but the water is still frigid. Our small boat bobs in the water as our captain, Brian Allen, scans our surroundings.

“Nothing.” He remarks with resignation.

We sigh, finish connecting our hoses and checking our gauges, then plunge into the icy water.

While others may visit the Puget Sound looking for orcas, I was here looking for bull kelp (Nereocystis leautkeana). Bull kelp is a large seaweed that attaches at the sea floor and floats on the surface, creating something akin to a forest underwater. And just like their terrestrial counterparts, kelp forests provide critical habitat for many species of marine animals. For millennia, the bull kelp forests of the Puget Sound provided bountiful food for people who lived in and traveled through these inland waters. But slowly and subtly, bull kelp beds started shrinking and disappearing. Now, the once-common sight of bull kelp bobbing on the waters’ surface is a rarity. The million-dollar question is, why?

I’m out on the boat with Jamey and Brian trying to answer that very question. Jamey is a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a federal agency charged with managing our nation’s marine resources. Our boat captain, Brian, works with the Puget Sound Restoration Fund, a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting and preserving marine ecosystems in the Puget Sound. Also involved are experts in remote sensing, Kate Tiedeman and Aniruddha Ghosh from the University of California-Davis, resource managers with the Washington Department of Natural Resources, and the many tribal nations whose ancestral lands abut the sound. The potential consequences of kelp loss at such a huge scale make this is an all-hands-on-deck situation.

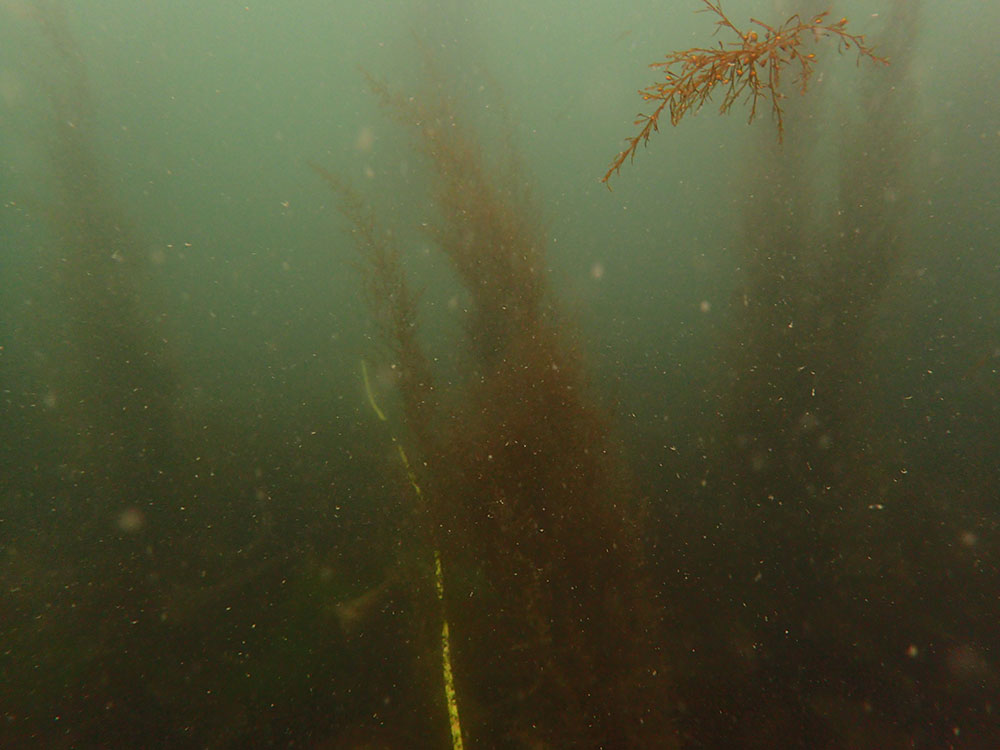

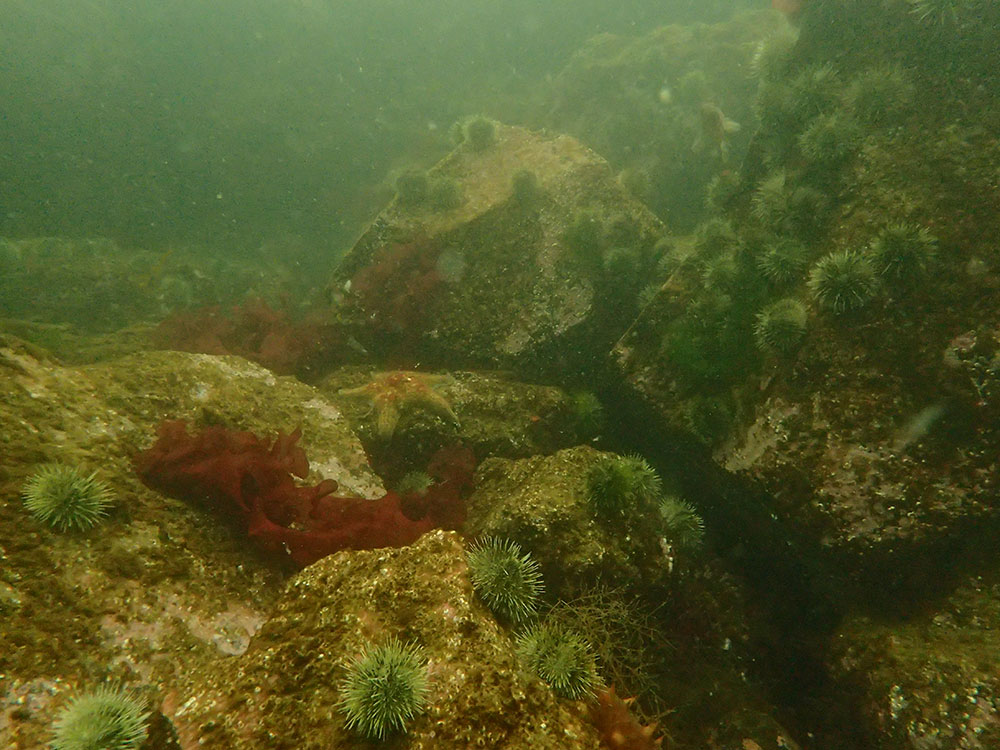

As Jamey and I settle onto the bottom with 25 feet of green-tinged water above us, I begin to understand why the cause of kelp disappearance remains so elusive. We visit three sites, all of which used to have bull kelp, none of which do now. The first site is covered in green urchins (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis), kelp-eating invertebrates infamous for their ability to turn kelp forests into barrens of rock. Maybe it’s all a giant urchin barren! The lightbulb alights in my head as I picture the millions of acres of urchin barren currently stretching across the Northern California coast. But the next site is covered in an invasive seaweed (Sargassum muticum) that dominates the canopy without an urchin in sight. Could bull kelp be outcompeted by the invasive? The lightbulb starts to flicker. The final site is a rich diversity of native algae with no urchins or invasive species, but none of these native algae grow to the surface and create the important underwater forest habitat. The light bulb flickers and dies. What is going on here?

Back on the boat, my eyes drift to the land surrounding the Puget Sound. It is scarred by clear-cut patches marking recent and decades-old logging sites. For over a century, people have denuded the steep hillsides in this rain-soaked region, leaving watersheds prone to landslides and rivers choked with mud. That mud combines with other land-based nutrients and pollutants and eventually travels to the sea where can reduce the light that bull kelp needs for energy and deposits those nutrients and pollutants, upsetting the careful natural balance which determines which species thrive and which suffer. Some of my colleagues and I think that this mud from clear-cut logging, combined with ever-warming temperatures from global warming, may be a major reason the kelp is disappearing. However, like anything in ecology, the full answer will be anything but straightforward.