Will Mussel Aquaculture Be Viable Along The California Coast?

Mussels are found the world over. Many native freshwater mussels are admired for their ability to clean our streams and rivers, while invasive ones (which are actually clams masquerading as mussels!) are reviled for voraciously eating plankton and clogging pipes. The shells and tissues of mussels are often used as monitoring instruments because they reliably record changes in the surrounding environment.

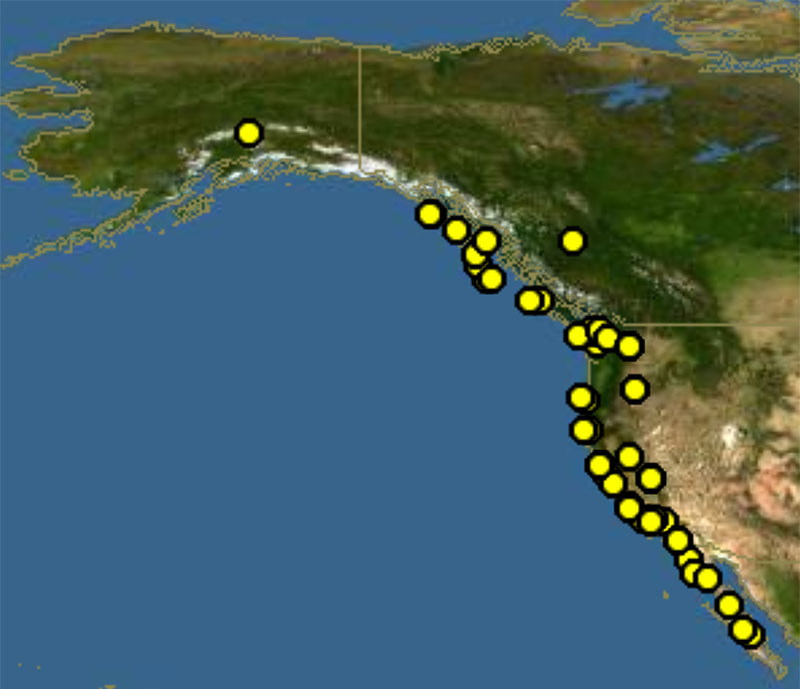

In western North America, tightly packed conglomerations of the California mussel span from southwest Alaska to the end of Baja California. And, archaeological evidence indicates that the indigenous peoples of western North America consumed these mussels 13,000 years before moules-frites appeared on seafood restaurant menus in Pacific coast backwaters.

In western North America, tightly packed conglomerations of the California mussel span from southwest Alaska to the end of Baja California. And, archaeological evidence indicates that the indigenous peoples of western North America consumed these mussels 13,000 years before moules-frites appeared on seafood restaurant menus in Pacific coast backwaters.

Although mussels have a rich tradition in European cuisine – going so far as to appear in Enlightenment-era art – oysters have reigned as the primary shellfish consumed throughout the United States, including in California. As demand for oysters grew and natural populations dwindled, the U.S. oyster industry transitioned from harvesting natural oyster beds to growing them in coastal waters (“aquaculture”). Oysters have been farmed in California since 1929, but mussels have been farmed in Europe since the 13th century. With global demands in seafood increasing, mussel farming – a $3 billion global industry – is now emerging along the California coast.

Aquaculture was responsible for nearly half of the seafood consumed in 2015, and farmed shellfish made up 10% of all seafood consumed that year. Mussels grow the most easily of all farmed shellfish, reaching market size within a year. They are incredibly nutritious; a single Blue Mussel contains only 290 calories, but has 40g of protein and 1,500mg of Omega-3 fatty acids. While these characteristics make mussels an ideal target for a profitable business and for securing food resources around the world, it is unclear how the changing climate will affect the success of these mussel farms.

Aquaculture was responsible for nearly half of the seafood consumed in 2015, and farmed shellfish made up 10% of all seafood consumed that year. Mussels grow the most easily of all farmed shellfish, reaching market size within a year. They are incredibly nutritious; a single Blue Mussel contains only 290 calories, but has 40g of protein and 1,500mg of Omega-3 fatty acids. While these characteristics make mussels an ideal target for a profitable business and for securing food resources around the world, it is unclear how the changing climate will affect the success of these mussel farms.

California’s coastline is on the frontlines of climate change. San Diego saw its warmest ocean temperatures this past summer, a toxic algal bloom closed the San Francisco Bay Area Dungeness Crab industry in 2015, and oyster and abalone farms are actively combatting acidifying waters. Mussels, like oysters and abalone, build a protective calcium carbonate shell to protect their soft tissues from the elements. In more acidic waters, mussels – especially young ones – have a hard time building their shells and the protein-laden byssal threads (“beards”) that they use to secure themselves to the rocky shore degrade. They are also incredibly sensitive to rises in temperature.

For my doctoral research at UC Davis, I plan to study how climate change will affect the mussel aquaculture industry. Because farmed mussels are often suspended on ropes using their byssal threads, I am interested in exploring whether warmer, more acidic waters will prevent mussels from staying attached to ropes and affect their overall production. Mussel aquaculture presents many opportunities in California and around the world, and I hope to use my research to make mussel farms an enduring and robust enterprise as the oceans continue to change.

For my doctoral research at UC Davis, I plan to study how climate change will affect the mussel aquaculture industry. Because farmed mussels are often suspended on ropes using their byssal threads, I am interested in exploring whether warmer, more acidic waters will prevent mussels from staying attached to ropes and affect their overall production. Mussel aquaculture presents many opportunities in California and around the world, and I hope to use my research to make mussel farms an enduring and robust enterprise as the oceans continue to change.